Hi! My name is Kate and I am from Oakville, Ontario! I am currently in my fourth year at the university of Guelph, majoring in Studio Art.

“The Artist is Present” Documentary Reflection

2. What have you learned about features of performance art based on Abramovic’s work? Name a few key features according to her precedents. Include an image to illustrate. Consider her quote, “When you perform it is a knife, and your blood, when you act it is a fake knife and ketchup”.

Some key features of performance art that I’ve learned through watching Marina Abramović’s work in her documentary include vulnerability and risk. Vulnerability appears in a literal sense, through nudity and the use of the body as a medium for self-expression, but also through the emotional rawness of Marina’s work. Her performances often draw from personal narratives, exploring past relationships or deeply personal themes she wishes to test or better understand. Another major feature of performance art is risk. Unlike acting, which is based in fiction, performance art blurs the line between art and reality. This idea is reflected in Marina’s quote: “When you perform, it is a knife and your blood. When you act, it is a fake knife and ketchup“. With acting, there is less at stake, nothing real to lose, and sometimes not much to gain. But in performance art, the artist often pushes their physical and mental boundaries to extreme and unimaginable levels. In her piece The Artist is Present, Marina sat silently across from anyone in the audience who chose to sit with her. Participants could stay for as long as they wanted, engaging in silent, face-to-face interaction. She became a mirror, offering each person her full attention, empathy, and presence. The emotional intensity of these encounters was profound, often leading to tears or deep reflection. Remarkably, Marina treated each individual with equal respect and care, taking on their emotional energy and making them feel truly seen, even as strangers. The reactions of the participants were authentic and deeply in-the-moment. One of the most powerful aspects of performance art is that the audience becomes part of the piece. There is no real script, and each performance is unique and unrepeatable. Often controversial, performance art usually carries a message or provokes thought, aiming to create a lasting impact.

3. Discuss ways performance art resists many museum and commercial artworld conventions. How does Abramovic solve/negotiate some of these challenges, and do you find these compromises add to, or undermine the ideas at play in her work?

Performance art resists many traditional museum and commercial art world conventions because it is not something tangible. Unlike a painting like the Mona Lisa, it isn’t meant to hang on a wall or be collected as an artifact. It is not static, it thrives on movement and interaction. Often, the artist’s body becomes the medium, and the audience serves as a participant or point of contact. Performance art challenges conventional definitions of art, often sparking the question: “What is art?” or “What makes something art?” Unlike traditional forms that may require years of technical training, performance art is driven more by purpose and intention. What matters most is having a cause you’re passionate about and a message you’re determined to express or explore. Rather than existing for passive consumption, performance art centers on experience, sometimes an uncomfortable one. It provokes engagement and encourages dialogue, giving the audience something to reflect on or even be unsettled by. Because it lacks physical form, performance art is fleeting; it can’t be repeated in the exact same way. This stands in stark contrast to traditional artworks that remain on display for decades, fixed and unchanging. Marina Abramović addresses the challenges of this impermanence by documenting her performances. In some of her exhibitions, she shows compilations of past works through video, allowing a broader audience to access experiences they may have missed in real time. In her documentary, we also see her teaching others to recreate some of her earlier performances, which were then presented as a live exhibition. These methods make her work more accessible. However, this also raises the question, by making performance art something you can re-watch, does it lose some of its unique impact? The “awe factor” of witnessing something live is diluted when it can be watched over and over again.

Assignment One: 1 KM

The Yarn Wall

Reflection

For my 1 km project, I decided to gather all the yarn I had lying around and measure out 39,370 inches—the equivalent of one kilometer. My ruler was 18 inches long, so I divided 39,370 by 18, which gave me approximately 2,187. That meant I had to measure my yarn 2,187 times. It was definitely time-consuming, but I think it was worth it in the end!

Once I had measured and unraveled all the yarn, it was time for the fun part. I began hanging it up on a blank wall in my room using masking tape. I started by attempting to create a flower, but quickly realized it was far too time-intensive. So instead, I shifted to hanging larger chunks of yarn to create a background that covered more space followed by adding in more details later.

I didn’t follow a plan, everything was guided by intuition. I taped the yarn wherever it felt right, and once the tape was down, I never moved it. I wanted the installation to feel organic and unedited, focusing on abstract shapes and loose ends.

What I found most fulfilling was making something tangible out of measurement, something we usually think of as numerical. Working with yarn allowed me to see the concept of measurement take shape in my own hands, inch by inch, in a slow process.

After receiving feedback during the critique, I do wish I had kept my video in real time instead of speeding it up. It would have better conveyed the slow, seemingly endless nature of the work, the feeling of constantly asking myself, “Is this it? Am I finally done?” It was a time-consuming process, but deeply rewarding.

Turning The Gestures of Everyday Life Into Art Reflection

1. Describe the work discussed in the article and the unique

challenges – as well as the unique gifts- that come with attempting to archive personal movements?

In the article discussing Katja Heitman’s work Motus Mori, she explores how each person expresses emotion through unique mannerisms and forms of touch, making every interaction deeply personal. It reminded me of an experiment I once saw on YouTube, where blindfolded individuals hugged a lineup of strangers, with one loved one hidden among them. Many could identify the person dear to them, showing how touch, as well as scent and texture, are deeply personalized. These unconscious habits often go unnoticed by the person themselves but are clearly recognized by those who know them well. Heitman believes that everyone has at least one gesture uniquely their own, highlighting her belief that “no two bodies move the same way.” One challenge she encountered in capturing this authenticity was during formal interviews, where participants became overly self-aware. As a result, their movements appeared filtered and polite, losing the candidness Heitman sought to document.

2. Discuss one or two examples of movements in the article – what strikes you about them?

Two movements described in the article that stood out to me were Tjan’s unconscious habit of making himself appear smaller in public and Arab’s constant knuckle-cracking. I admired how, after becoming aware of this tendency, Tjan chose to challenge it by buying the brightest jacket he could find, intentionally making his presence louder and impossible to overlook. Similarly, I found it powerful that Arab gained a new understanding of his so-called “anxiety hands.” What may have once seemed like a negative, his habitual knuckle-cracking is now something he views differently, something personal and uniquely his, a gesture he can take ownership of rather than feel ashamed about.

3. Describe the habitual movements/unconscious gestures, tics etc. of 3 people you know well. How do individual body parts move, and how does the whole body interact? What about facial expressions, and emotional valence of the movement? How does body type inform the movement? What do these examples of small movements mean and imply?

One habitual movement my little sister does is twirl her hair into a tight twist, then thread the end through the center and pull it until it snaps with a loud pop. It honestly drives me crazy—I’m always telling her to stop, but she never realizes she’s doing it! It usually happens when we’re deep in conversation and she’s fully focused. Her fingers and hair move in a repetitive rhythm, almost like a little dance.

One habitual gesture my mom does is unconsciously bites her pointer fingernail when she’s thinking hard or feeling slightly nervous. I don’t think she’s aware of it, but for me, it’s a clear sign that she’s overthinking or feeling uneasy.

My best friend has her own set of stress signals. She cracks her knuckles on both hands when she’s overwhelmed, moving quickly from finger to finger and returning to any that didn’t crack the first time. Sometimes her face even flushes slightly while she does it—another subtle sign that she’s under pressure.

AGG Field Trip Reflection

The first piece I chose to reflect on is Bison Survival Story Robe by Adrian Stimson. This work tells the story of the Pablo-Allard herd, which played a crucial role in repopulating the nearly extinct bison species. Stimson depicts this powerful history through a pictograph painting on the robe, highlighting the resilience and survival of the bison. I was moved by this depiction. The bison were once hunted to the brink of extinction, yet a small group managed to survive and ultimately restore their population. Their story is one of strength, endurance, and hope. This piece has inspired me to pay closer attention to stories of resilience especially those connected to the environment. It reminds me that even small efforts can lead to meaningful recovery and change.

The second piece I chose was by artist Sheri Osden Nault. When I first encountered the work, I mistook the sculptures for real animal skulls. However, I soon learned they were actually crafted from unfired clay mixed with seeds and soil. Molded from an actual bison skull, the sculptures are life-sized, which gives them a strikingly realistic appearance. Each skull is hollow and designed to be filled with mulch before being placed in the artist’s garden. Over time, they will slowly decompose and return to the earth, allowing wildflowers and local medicinal plants to grow from within them. It’s a powerful representation of the circle of life, cultural influence and giving back to the Earth, which gives us so much in return. I’m very inspired by the way this piece captures transformation over time. It reminds me of the ways in which life, death, and regeneration are connected.

Video Assignment: When Fragility Meets Destruction

Video 1:

Video 2:

Animation:

Reflection

Our gesture involved plucking petals from a bouquet of flowers, an action often seen as “cliché,” typically associated with hyper-feminine characters in films uttering the phrase, “He loves me, he loves me not.” We wanted to challenge and subvert this picturesque image of delicate beauty by, for lack of a better word, destroying it.

In our first unedited video, we captured the simple act of stripping a flower of its petals one by one. Visually, it’s quite a beautiful image, the petals slowly drifting out of frame. We deliberately chose the most socially accepted “feminine” flower we could find, one that was pink with lots of petals. The pacing is slow and unhurried, creating enough space between each pluck to almost imagine the iconic words being spoken.

For our second video, we took a very different approach. We shot a variety of clips and edited them into fast, jarring cuts to create a sense of chaos, almost aggression. My slow, gentle plucking evolved into breaking, twisting, snapping, pulling, and ripping. Instead of petals gracefully falling like they’re drifting into sleep, they’re violently thrown behind me, bouncing off the floor. In one moment, I cradle the flowers softly in my arms; in the next, the stems are snapped in half. Rather than removing petals one at a time, I grab entire blooms and tear them apart. In doing this, we aimed to challenge traditional notions of femininity by adopting a more “masculine” approach. The final shot shows petals scattered at my feet as I walk out of the frame, leaving them behind as if they are something to be discarded.

We also paid close attention to sound while filming. We chose movements that produced the loudest, most impactful noises, which complemented the fast-paced editing. As a result, the second video developed a kind of rhythm, with a range of sounds, some soft and sprinkling, others sharp and snapping. To enhance this rhythm and add emphasis, we repeated certain clips multiple times throughout the video.

One of the most enjoyable parts of the project was filming in the studio. We had fun experimenting with the camera and finding interesting shots and angles. With Michelle’s guidance, we noticed after importing our footage into DaVinci Resolve that, while the lighting was even and well-executed, the contrast was a bit high. We adjusted the settings in the software, toning it down to improve clarity and crispness.

For the animation, we decided to take a more realistic approach, staying close to the look and feel of the original video. We zoomed in and cropped the clips to focus attention on the movement happening in my hands. In hindsight, the section we chose to animate may not have been the most effective, particularly in how it looked when reversed for the loop. The difference between the original and the reversed version wasn’t as striking as we’d hoped, so that part fell a little flat visually in my opinion.

Pauline Oliveros Documentary

Reflection Question:

Reflect on your own experiences of listening, to sound, to others, to your environment, or to yourself. How does Oliveros’s idea of deep listening challenge the way you typically give attention? In what ways might listening through your whole body, or approaching sound as a form of play and research, change your understanding of connection, communication, or creativity?

Oliveros’s idea of Deep Listening challenges the way I typically give attention to the sounds around me. It makes me realize that I often experience sound passively, hearing voices in conversation, music playing in the background, or the ambient noises of nature like wind or rustling trees. I notice these sounds only on the surface, as if they’re just happening around me all the time, but I’m not truly listening to them, not noticing how they make me feel, their rhythms and pauses, the power of silence or the relationships they create.

For Oliveros, Deep Listening is about cultivating a deeper awareness. It’s not about concentrating harder or trying to analyze every vibration, but about opening yourself up to the subtle sounds that usually go unnoticed. Sound, for her, becomes a kind of meditation, a form of play and a way of being present with herself and her environment. It’s a moment where she doesn’t feel separate from the world, but rather part of an experience happening in real time. If I were to listen through my whole body, I think that creativity might become more fluid and spontaneous. Deep Listening, isn’t just a practice of attention, it’s a way of being that nurtures curiosity, and a deeper sense of belonging.

One moment from the Deep Listening documentary that really shifted my understanding was when Oliveros invited a deaf man to act as the composer for a performance. Instead of seeing his deafness as a limitation, she treated it as another mode of perception, another way of being in relationship with sound. The man “composed” by feeling the vibrations of instruments and bodies, using his own sensory experiences to guide the musicians. For Oliveros, this wasn’t experimental for its own sake, it was an exploration of how true listening can transcend hearing, how sound is something we can all experience through our entire bodies and through the space we share.

Audio Assignment

First Words

For our audio assignment, Grace and I called a series of people with varying relationships to ourselves, from those closest to us, like our moms, to complete strangers, like a Domino’s Pizza employee. We reached out to people we hadn’t spoken to in a long time, as well as friends we’re close to but rarely call. Each call was met with a range of emotions, confusion, annoyance, excitement, and warmth.

This experience made me pay close attention to how people answered the phone and how much that small moment revealed about both them and our relationship. It’s something I had never really noticed before. We found it quite awkward and uncomfortable to call people just for an assignment, especially when we had to explain that we were calling only to record their greeting. It was equally awkward when we called someone we didn’t know and weren’t sure what to say.

Through this process, I realized I should call my loved ones more often so that hearing from me isn’t such a rare surprise. It was genuinely sweet to hear the excitement in their voices when they picked up the phone. Sharing those recordings with the class felt surprisingly vulnerable, like revealing an intimate part of my personal life that’s usually private. Still, I think the topic made for an engaging and relatable audio piece, one that kept you listening and waiting for the next “hello.”

Conceptual Portrait Proposal

Idea #1: Capturing the trace of my roommates presence through a collage of photographs

Examples of images:

- Their unmade bed- capturing the outline of their indent in the mattress/pillow

- Lipstick stain on a mug

- Crumbs left over after a meal

- Footprints

- Clothes left on the floor after they have changed

- Steamy mirror with the silhouette of where they wiped to see their reflection

- Handprints on a foggy window

- Slippers by the door

- Half read book left open, spine curved

- favourite snack wrapper in the garbage

- To-do list/scribbled notes

- Depicting what someone has left behind

- Following their movements and unique marks that come out of things being touched

- The quiet scraps of someones life

I was inspired by the works of Felix Gonzalez-Torres, whose installations are often minimal and still, yet evoke a profound emotional weight. His piece “Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.)” particularly resonated with me. In it, a pile of individually wrapped candies represents his late husband, Ross, who tragically passed away from AIDS. The pile originally weighed 175 pounds, the healthy weight of Ross’s body, and viewers were invited to take pieces of candy, slowly depleting the pile. This simple but powerful act mirrored the physical deterioration caused by the disease. The work’s quiet simplicity makes its emotional impact all the more profound.

Idea #2: The essence of my roommate depicted through her favourite outfit

- Have my roommate select an outfit from her closet that she feels truly represents her identity.

- Have my other roommates, along with the outfit’s owner, each try on the same outfit one by one.

- Film each person walking into frame wearing the outfit, cropping their heads out of the shot to remove explicit identity and highlight how it is expressed instead through movement, posture, and presence.

- Present the video as a guessing game, inviting the audience to determine who the true owner of the outfit might be based on body language, comfort, and confidence.

- Edit the footage to appear as one continuous clip of people walking in and out of frame, blurring distinctions between individuals.

- Emphasize how clothing carries memory and self-expression, though the outfit remains the same, it communicates something entirely different on each person.

I was inspired by the work of an artist who created a kind of “game” through their art, fabricating a story that unfolded within a museum setting using realistic, made-up artifacts. The goal was to convince the audience that the story was true, only to reveal at the end that it was entirely fabricated. I really like the idea of this final reveal and the way it makes the experience more interactive and engaging for the audience.

Idea #3- Hands

- Hands are the closest body part we have in terms of revealing ones true identity- hold as much individuality as a face, without revealing someone fully

- Hand becomes a stand in for the self (personal yet revealing part of the body)

- What the hands say about them versus what a face would show

- Biometrics- unique physical or behavioural measurements used for identification (fingerprints, vein patterns, skin creases, overall hand geometry)

- These patterns are established at birth and never change

- Physical condition of hands can reveal a person’s background or work history (for example, calloused, rough hands= manual labour and soft, dainty hands= life of leisure)- Narrative clues

- These details turn the hands into visual evidence of lived experience.

- Non verbal communication- insight into a persons habits and personality (nail biting, fidgeting, nervous gestures)

- Hands carry traces of lived experience, the way nails are kept, the presence of rings, freckles, scars, or softness. Each mark becomes evidence of the routines, histories, and habits that shape a person.

- Photographed each of my roommates hands as they were in that moment

- We combined different parts of our hands to create a single, composite hand, one that reflects how we share the same physical features yet remain distinctly individual. At the same time, the merged hand suggests the subtle ways we absorb the influence of the people we surround ourselves with.

- We absorb habits, mannerisms, and ways of being from our environment and the people around us

- Collaged format- interconnectivity of our lives, they are visually communicating with dialogue, gestures and hand movement (almost like the steps of a handshake)

Conceptual Portrait

Reflection

Grace and I began by thinking about a body part, other than the face, that could reveal something meaningful about identity and that all of our roommates shared in common. We landed on the hands. We were fascinated by how hands can tell a story about someone’s lived experience; calluses that develop from years of labour, or the soft, delicate hands of someone who lives a life of leisure. We felt that hands say a great deal about a person.

We were also drawn to the distinct, unchanging markings people have on their hands, moles, freckles, palm creases, fingerprints, vein patterns, and overall hand geometry. These details are established at birth and remain constant, making them powerful forms of physical identification.

Hand gestures, too, serve as behavioural measurements, and this became the foundation or system we followed throughout our conceptual portrait. Observing hand movements, gestures, and positions can reveal a person’s emotions, thoughts, intentions, and even personality traits. These nonverbal cues often communicate what someone may not consciously express. Nervous tapping, fidgeting, or rubbing the hands can signal stress or impatience; still, controlled hands may reflect reservation; open palms tend to suggest honesty, openness, and trustworthiness.

We wanted our images to reflect this idea of movement, expression, and subtle communication. The collage format, overlapping photographs pointing in different directions, was our way of creating dialogue between the hands. To us, the arrangement resembled the shifting steps of a handshake exchanged between hands that don’t actually know one another.

We were also interested in showing the connectivity between the two groups of people we photographed, our roommates, who don’t know each other but are indirectly connected through our friendship. It’s fascinating how you unconsciously adopt the mannerisms of the people you spend the most time with. I might pick up a gesture from Grace, who may have learned it from her roommate, and so on. A gesture travels from person to person, yet its origin becomes impossible to trace. This creates a chain of connection, a shared language of movement between individuals who may be strangers to each other but are linked through these subtle hand gestures.

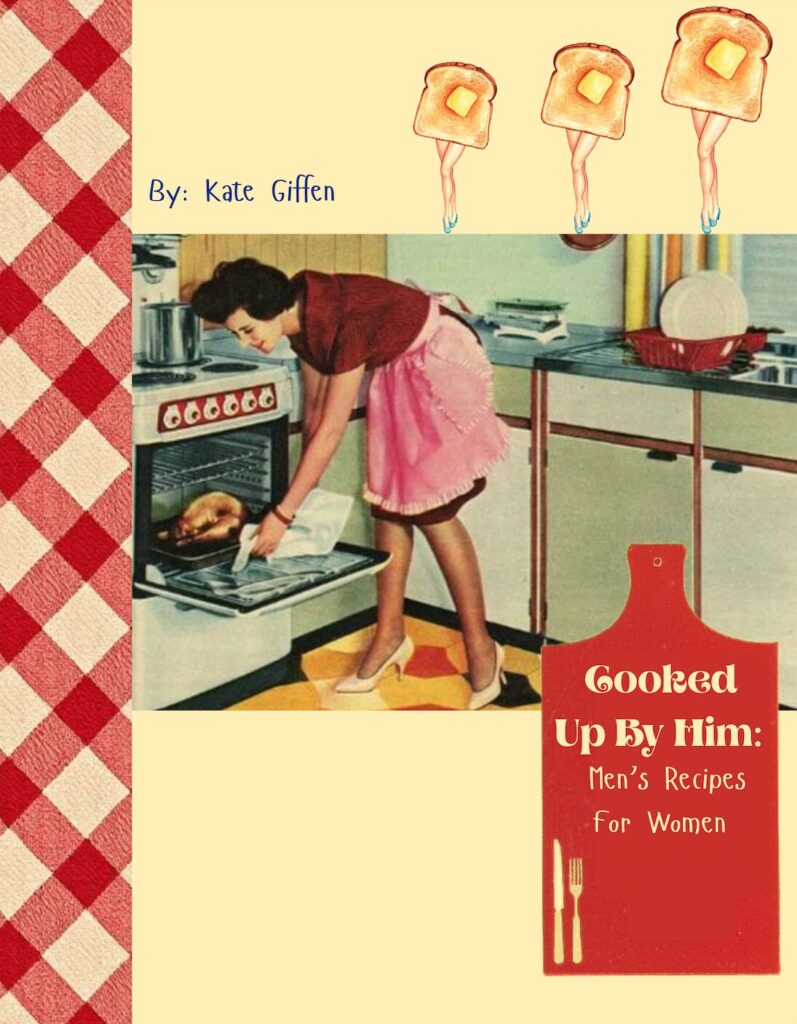

Counter-Archive Zine: “Cooked Up By Him: Men’s Recipes for Women”

The zine I created is a feminist project designed to replicate a 1950s-style cookbook. It draws on the era of the housewife and highlights the sexism, stereotypes, expectations, and limitations imposed on women by men at the time. Through a sarcastic and humorous tone, the zine critiques these serious historical issues. Each recipe features a classic 1950s housewife dish, reimagined with ingredients and instructions that expose and challenge the gendered expectations of the period.